🌈 Lava Lamps: The Groovy Glow of the Psychedelic Era

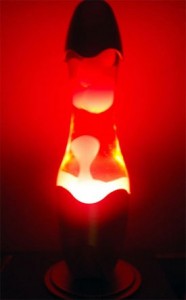

If there was ever a lamp that screamed “Turn on, tune in, and chill out,” it was the Lava Lamp. Whether you were stoned, straight, or just slightly spaced out from too much orange soda, these glowing tubes of slow-motion magic were the crown jewel of any 60s or 70s den, dorm, or basement hangout.

Blob, rise, melt, repeat. It was like watching a hypnotic dance of molten jellyfish trapped in a science fair experiment—and somehow, it made perfect sense.

💡 Birth of a Bubbling Legend

Believe it or not, the Lava Lamp wasn’t born in a head shop or dreamt up at Woodstock. It started in the UK, when inventor Edward Craven Walker spotted a quirky homemade lamp bubbling away in a pub. That simple wax-and-liquid contraption sparked an idea.

By 1965, Walker brought his invention—originally dubbed the Astro Lamp—to a trade show in Hamburg. There, a savvy American businessman named Adolph Wertheimer saw it, bought the rights, and began manufacturing them in the U.S. under the name “Lava Lite.” And the rest is groovy history.

🔥 How It Works: Science Meets Swag

The setup? Pretty simple.

- A tall, narrow glass bottle

- A clear liquid (usually mineral oil or water-based)

- A waxy blob of magic

- A 25 to 40-watt lightbulb in the base

Flip the switch, and the bulb heats the wax. It melts, expands, and floats up. As it cools at the top, it shrinks and sinks back down. The result? A mesmerizing loop of psychedelic wax ballet that never repeats the same way twice.

🎥 “How How Do They Make Lava Lamps?”]

🧠 Mind Expansion—No Batteries (or Substances) Required

Let’s be honest. The Lava Lamp was the perfect backdrop for the psychedelic revolution. While your ears were tuned to Hendrix or Jefferson Airplane, your eyes could drift into the ebb and flow of that glowing, gooey dance. It wasn’t just decoration—it was meditation.

As Edward Walker himself once said:

“If you buy my lamp, you won’t need drugs… I think it will always be popular. It’s like the cycle of life. It grows, breaks up, falls down, and then starts all over again.”

No wonder these lamps became icons of hippie culture, head shops, and late-night dorm room chats about “the meaning of it all.”

♻️ Still Glowing Strong

Despite being a product of the psychedelic age, Lava Lamps never went out of style. They’ve gone from counterculture accessory to mainstream home décor, now sold everywhere from department stores to online marketplaces. Walk into a Goodwill or vintage store, and odds are, one’s sitting on a dusty shelf, just waiting to bubble again.

Modern versions use safer materials, better bulbs, and come in all sorts of colors and sizes—but they still work the same way. Flip the switch, let it warm up, and you’re back in that magical headspace of rising blobs and melting time.

🌟 The Eternal Lamp of Cool

In a world full of digital distractions and high-speed everything, the Lava Lamp is a glowing reminder to slow down, chill out, and let your thoughts float for a while. Whether you’re a nostalgia-loving boomer or a Gen Z kid discovering vinyl and incense, the Lava Lamp still brings that same vibe:

Groovy. Warm. Weird. Wonderful.