✌️ From Beatniks to Hippies: Rock and Roll’s Counterculture Roots

The Golden Age of Rock didn’t just soundtrack a generation—it came with its own cast of colorful characters. And while some of the older folks might have lumped them all together under “dirty, unwashed scum” (charming, right?), we know better.

Sure, maybe a few hippies forgot to shower. And yes, beatniks loved their black turtlenecks and bongo drums. But these were two distinct cultural tribes, and both played important roles in shaping the look, sound, and soul of rock and roll.

🥁 The Beatniks: Jazz, Bongo Drums, and Cool Detachment

Before hippies hit the scene, there were the Beatniks.

The name sprouted from the Beat Generation, a term coined by writer Jack Kerouac in the late 1940s to describe a group of post-war bohemians who were disillusioned with mainstream values and spiritually adrift. “Beat” referred to both the musical rhythm they loved—usually jazz—and the sense of being “beat down” by society.

Then came Sputnik, the Soviet satellite that launched into orbit in 1957. The U.S. was stunned, and someone jokingly slapped the “-nik” suffix onto “Beat” to form a new word: Beatnik. It stuck.

🧔♂️ The Beatnik Look?

Goatee, beret, dark shades, and a turtleneck for the guys.

🖤 For the gals? Black leotards, long straight hair, and serious existential vibes.

Beatniks hung out in coffeehouses, read poetry aloud, and sipped espresso while discussing the meaning of life. They “played it cool,” spoke in jazz slang, and tried very hard not to care what anyone thought of them.

They weren’t wild—they were wary. But they laid the groundwork for what was coming next.

☮️ Enter the Hippies: Tie-Dye, Rock, and Revolution

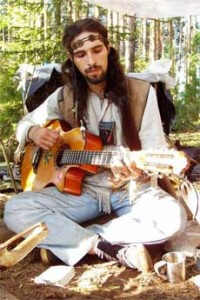

In the early 1960s, the cultural tides shifted again. A new generation emerged—less interested in existentialism and bebop, and more into psychedelics, rock and roll, and radical change. They became known as Hippies, or the Hip Generation.

Although a few Beatniks morphed into Hippies (Kerouac, for example, didn’t love the new crowd), the two groups were very different.

Where the Beats were low-key and literary, the Hippies were vibrant and visual.

Where Beatniks whispered poetry, Hippies shouted protest slogans.

But the biggest difference? The music.

- Beatniks loved jazz.

- Hippies lived for rock and roll.

And not just any rock. We’re talking psychedelic jams, folk-rock anthems, and electric rebellion. This was the era of The Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin, Jefferson Airplane, and Jimi Hendrix. Music wasn’t just a background to the movement—it was the movement.

🌍 Culture Clash and the Anti-Everything Attitude

The hippies had opinions. Lots of them.

They were anti-war, anti-materialism, and anti-establishment—which didn’t win them many fans among middle-class, middle-aged Americans watching the 6 o’clock news. But to the youth? The hippies were heroes.

Some dropped out entirely, heading for communes or hitchhiking across the country in flower-painted vans. Others took to the streets, joining marches, protesting the Vietnam War, and clashing with police during events like the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago.

Whether political or just peaceful, hippies believed in love, peace, self-expression, and (of course) great music.

🗺️ The Hubs of Hippie Culture

Like all cultural movements, the hippie wave had its capitals—cities where music, art, politics, and counterculture collided in technicolor brilliance.

- Greenwich Village, New York – The East Coast’s hub for folk music and progressive thought. Bob Dylan got his start here in tiny coffee shops.

- Venice Beach, Los Angeles – Known for its beachside bohemia, beat poets, and early rock experiments.

- Haight-Ashbury, San Francisco – The epicenter of the Summer of Love, 1967. Here, psychedelic music, flower crowns, and anti-war sentiment all came together under one hazy sky.

📺 Watch: Scott McKenzie – “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)”

🎶 Beatniks vs. Hippies: Not the Same, But on the Same Path

- Beatniks questioned society quietly.

- Hippies shouted their discontent with flower power and amplifiers.

The Beats laid the philosophical foundation; the Hippies added color, chaos, and a killer soundtrack.

Together, they helped fuel a cultural revolution—one that still influences art, music, politics, and fashion today.

🎸 Final Thought: More Than Just Dirty Hair and Bongo Drums

Sure, some of them could’ve used a shower. But the counterculture wasn’t about hygiene—it was about freedom, expression, and resistance.

From smoky poetry readings to open-air festivals with walls of sound, both Beatniks and Hippies played their part in shaping the Golden Age of Rock. And if that meant wearing a beret or growing your hair past your shoulders?

Well, that was just part of being cool, man.

Read more about Beatniks

Read more about the Hippie Movement

More about The Beat Generation